SQUATS FOR BOXING

The squat is a frequently programmed exercise in many strength and conditioning programs and is prescribed with the aim of improving lower body force production and the rate at which this force is developed. These aspects of performance are important as they are key determinants of performance in ‘explosive’ actions such as sprinting and jumping.

Performing a heavy back squat or any other squat variation may initially seem worlds apart from throwing a punch in the ring, however we can achieve general strength adaptations that can be transferred to the punching action by performing compound lifts such as the back squat.

BENEFITS OF THE SQUAT

The squat is used to develop lower body maximal force production and rate of force development.

Squat variations also overload the core region, helping to develop trunk mass which is one of the main contributors to the punch.

The squat promotes forceful hip extension which is a key component of any punch in terms of maximising force transfer from the floor, through the core and to the upper body.

Developing the core contributes to improved rotational speed and effective mass during the punching action.

A large eccentric demand on the glutes, quads and hamstrings during squat variations, improves the stretch-shortening cycle of the lower body, enhancing rate of force development and impulse as well plays an indirect role in reducing injury risk.

Lastly, multiple studies demonstrate improvements in jump height using the squat and as we know through our own research, boxers who jump higher tend to punch harder!

SQUAT CONSIDERATIONS FOR BOXERS AND COMBAT SPORT ATHLETES

Whilst the squat is a hugely beneficial exercise for boxers and can have an impact on their overall athleticism, it’s important that we maximise the safety and effectiveness of this key lift.

Some of the considerations to be aware of when implementing the squat with boxers include:

Knee dominant athletes

Boxers tend to display weakness in the posterior chain due to a lack of strength training, high running volumes with poor technique and prolonged periods of time in a flexed position as a result of the boxing stance.

Weakness in the posterior chain can therefore significantly hinder squat ability and an athletes tolerance to high loads. Therefore, continual performance of the squat without considering the underdevelopment of the posterior chain may exacerbate anterior or knee dominance, increasing the chances of injury.

Poor Postural Control

This is largely a consequence of a lack of structured strength training being performed throughout the boxer’s formative years and can have a negative impact on core bracing as well as lower back position in the bottom of a squat.

Weak Posterior Shoulders

The rounded posture associated with the boxing stance and the high punching volumes performed in training means boxers can become anterior dominant in the upper body. This results in weakness in the posterior shoulder region which can impair shoulder mobility, making it difficult for boxers to set themselves in a strong position under the bar.

To compensate for this lack in shoulder mobility, boxers will tend to extend the lower back or flare their rib cage which will significantly reduce core tension and protection of the spinal column when squatting.

Uni-Lateral Imbalances

Due to prolonged periods in a split stance, boxers will tend to have one lower limb stronger than the other. Boxers tend to shift most of their weight on their back leg (60%:40%, back leg; front leg), in order to maintain a rhythmical ‘step’ and balance and to be able to react to the opponents’ advances efficiently.

This will ultimately lead to imbalances in strength, eccentric control and mobility between limbs and tends to translate to a noticeable hip shift during the descent of a squat which suggests the athlete is compensating through their stronger side in order to control the load.

High Eccentric Demand

Whilst a high eccentric demand is a benefit of squat variations, this can lead to excessive muscle soreness for most athletes, particularly boxers.

Boxers tend to undertake extremely high training loads and recovery is often impaired as a result of adhering to a negative energy balance or calorie deficit in order to make weight. Therefore, boxers are more susceptible to severe muscle soreness which can restrict movement during technical training and conditioning and incrase the risk of injury.

SQUAT PROGRAMMING FOR BOXING AND COMBAT SPORT ATHLETES

We’ve discussed the benefits of the squat and key considerations when implementing the squat with boxers and combat sport athletes.

But how do we maximise safety and effectiveness of the squat in an S&C program? What are the appropriate regressions and progressions that should be performed? And when should we incorporate a given variation?

These are questions we have asked ourselves as practitioners in the past and ones that we are constantly asked by athletes, students and those eager to learn about our training methods.

With that said, the following sections will focus on:

How we develop proficient technique in the squat pattern at boxing science.

The variations of the squat and how we integrate these into specific phases of an athletes strength training journey.

How to program these squat variations.

Squat Mastery

Learning the Movement

In the initial stages, we focus on the athlete’s movement and learning how to squat with bodyweight and with light loads.

Two exercises that are prominent in this phase include the overhead squat and the goblet squat.

The overhead squat is a key part of our testing battery and is used to assess the athlete’s ankle, hip and shoulder mobility along with their core stability.

We also use the overhead squat in our training programs as a teaching tool for the squat pattern.

If you can master the overhead squat, you will more than likely be proficient at every other squat variation.

We also use the goblet squat to enable the athlete to learn the movement pattern whilst introducing a low-grade strength stimulus as well as core loading to lay the foundations for future phases.

Loading the Movement

Once sound technique has been established, we want to find ways of continually refining squat technique whilst beginning to achieve some noticeable strength gains.

Exercises that fit nicely into this phase include the landmine squat, box squat, pause squat and safety bar squat.

The landmine squat is an excellent progression from the goblet squat as it allows for higher loads whilst maintaining that front loaded position to avoid undue stress on the spine.

The box squat and pause squat enable the athlete to become accustomed to axial loading with the bar on the back.

These variations essentially segment the full back squat lift, making it easier for the athlete to tolerate increased loading and understand the desired positions during a squat.

The safety bar back squat is of particular benefit for athletes who might be restricted in the shoulder region. With the handles parallel to each other and positioned on the trapezius muscle group, the athlete can create sufficient core tension, obtain a substantial strength stimulus as the structure of the bar facilitates high loading potential and refine technique.

Maximally Loading The Movement

Once the athlete has been gradually exposed to higher loads and maintains his/her technique we can then aim to develop maximal strength and improve overall force production.

To get stronger we need to lift HEAVY…

Therefore, exercises in this phase should allow the athletes to lift the heaviest load possible without sacrificing technique and postural control.

Our go to lift during this phase is the barbell back squat, simply because out of all the squat variations, athletes can typically lift the heaviest loads during the barbell back squat.

To really drive maximal strength adaptations we also use Anderson Squats, which place complete emphasis on the concentric portion of the squat.

Due to the absence of an eccentric component athletes can lift even heavier, impart greater stress on the neuromuscular system and achieve greater strength gains.

This is a particularly useful lift if forced into a short training camp, where the technical training and sparring loads are high from the outset, as we can minimise soreness through elimination of the eccentric portion of the squat and still achieve significant improvements in maximal strength.

THE SQUAT AND THE STRENGTH TRAINING JOURNEY

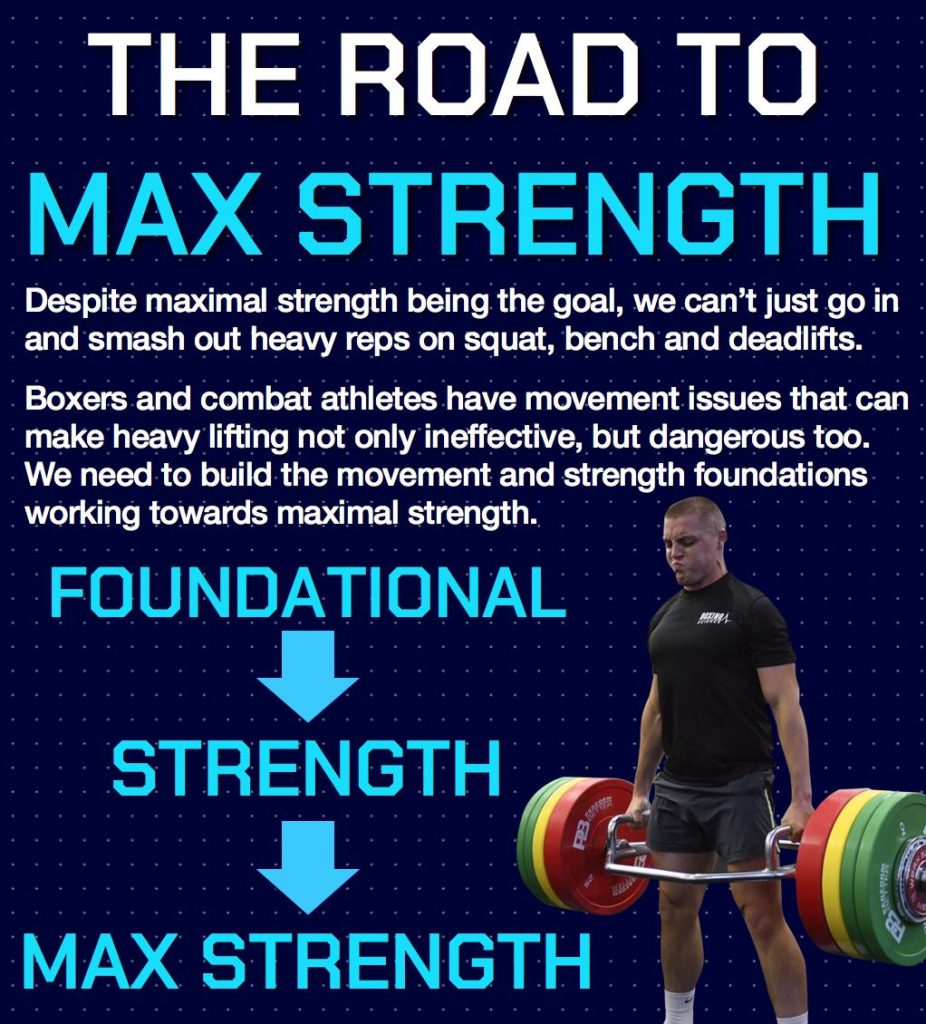

With any athlete, we try and work towards maximal strength training on each of the key lifts. This is because improving maximal force production can have an indirect impact on rate of force development and those who produce higher magnitudes of force tend to generate this force quicker.

As we’ve discussed previously, high rates of force development are desirable for delivering sharp, punishing blows to the opponent.

It is important, however, to gradually expose athletes to maximal loads and therefore our strength training journey for the key lifts consists of three phases:

Foundational Strength, Strength Development and Maximal Strength.

Heres how we program squat variations in accordance with aims of these phases:

Foundational Strength

The aim of this phase is to establish sound technique and movement competency that will set the foundation for future phases.

Progressing the load is not a top priority during this phase, instead manipulating the difficulty of the exercise should be used as the primary means of progression.

Incorporating pauses, different tempos and variations in the range of motion are appropriate.

The overhead squat and goblet squat tend to be programmed during this phase.

10-12 Reps x 3-4 Sets.

Strength Development

In this phase we are introducing higher loads whilst still considering technique as a top priority.

The landmine squat, pause squat and box squat are appropriate variations to include in this phase as they allow for increased loading furthering the athlete’s understanding of efficient squat technique.

These variations may also feature in maximal strength phases with athletes who still display movement and mobility issues when performing the squat pattern.

5-8 Reps x 3-4 Sets.

Maximal Strength

As we said previously, maximal strength phases should consist of near maximal, maximal, and even supra-maximal (partial range lifts) loads to drive improvements in force production capacity.

The back squat and Anderson squat are our staple squat variations during maximal strength training phases. These lifts enable athletes to lift the heaviest loads whilst maintaining technique and are therefore optimal for this phase.

3-5 Reps x 3-5 Sets

SUMMARY

The squat pattern is a key exercise in many S&C programs for developing lower body strength and rate of force development.

When programming the squat for boxers and combat sport athletes it’s important to consider their strength training background, muscle imbalances and movement limitations.

The squat pattern should be coached from a technical mastery perspective initially before adding load.

FIND OUT MORE IN OUR 45-MINUTE SQUAT MASTERY ON THE BOXING SCIENCE MEMBERSHIP