PROTECTING THE BOXER’S SHOULDER

The shoulder complex is an extremely important joint for boxing, considering it’s significant influence on the punching action.

However, with boxers throwing thousands of punches per week and across training camps, the enormous activity of the shoulder heightens the risk of injury to this area.

Therefore, as a strength and conditioning coach, it is important to have strategies in place that enable boxer’s to prepare their shoulder joints for the demands of boxing whilst reducing the occurrence of injury.

This article will discuss:

The anatomy of the shoulder and relevance to boxing.

How we target and improve shoulder mobility at Boxing Science.

Practical examples of how to protect the boxer’s shoulder during strength sessions.

SHOULDER ANATOMY

Compared to the other joints of the body the shoulder joint is particularly susceptible to injury.

This is primarily due to the large range of motion available at this joint and it is often said that the joint’s excessive mobility contributes to its vulnerability.

Additionally, the glenoid cavity which holds the humerus is not considered a true socket and therefore makes the shoulder joint less stable than other ball and socket joints such as the hip.

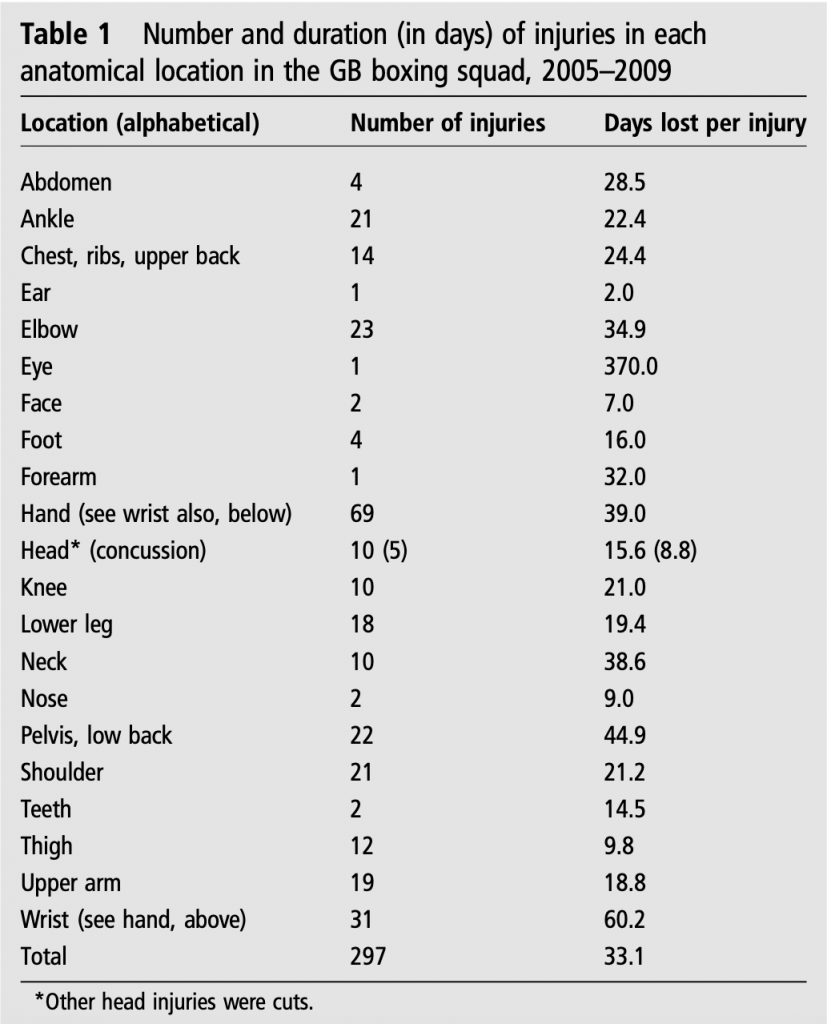

Along with injuries to the hand and elbow, the shoulder has been highlighted as one of the most commonly affected areas for boxers.

Injuries to joints such as these tend to occur in training due to repeated exposure to micro-traumas associated with large punching volumes.

ANATOMY OF THE SHOULDER

The shoulder joint is categorised as a synovial ball and socket joint and consists of the the glenoid fossa, head of the humerus and glenoid labrum.

The “ball” of this joint is the humeral head and sits into the “socket” which is the glenoid cavity.

The fossa and labrum, located within the glenoid cavity, are responsible for maintaining the position of the humeral head.

The humeral head, however, is three to four times larger than the surface of the glenoid fossa and thus only a third of the humeral head is ever in contact with the fossa and labrum.

Though this allows for considerably large ranges of motion it also compromises joint stability.

Stability of the shoulder joint is mainly provided by the rotator cuff muscles and other surrounding connective tissues such as the labrum.

Among boxers, labrum and rotator cuff tears are highly prevalent due to the great demands placed on these joint stabilisers in large punching volumes performed in training and competition along with a lack of emphasis on adequate shoulder prehab/activation.

With any injury, prevention is always better than cure, however avoiding injuries to the shoulder for boxers is particularly important for boxing given the importance of this joint to success in the sport.

Although the context of each injury is different, the consequences of shoulder injury for boxer can be severe including disruptions to careers, affecting performances, cancellation of fights (some big pay days) and impaired performance in subsequent training camps

Some athletes are more unlucky than others when it comes to injuries, but the likelihood of these occurring can be reduced by mobilising, stabilising and strengthening the shoulder joint.

SHOULDER MOBILITY

“Hands up, chin down” is often the coaching point to a defensive guard, requiring rounding the upper back and shrugging the shoulders.

If you’re throwing 100’s of punches thrown in a week’s training, the anterior shoulder and trapezius muscles can become over-active.

This alone can cause shoulder mobility issues for boxers. Large volumes of strength exercises like press ups and shoulder press further confound the issue meaning shoulder mobility should be a focus for boxers.

Poor shoulder mobility often creates over-active anterior deltoids and upper traps, causing the middle and lower traps become weak which affects the natural movement of the shoulder and arm.

This can also cause shoulder impingement, rotator cuff weakness and lower-back injuries.

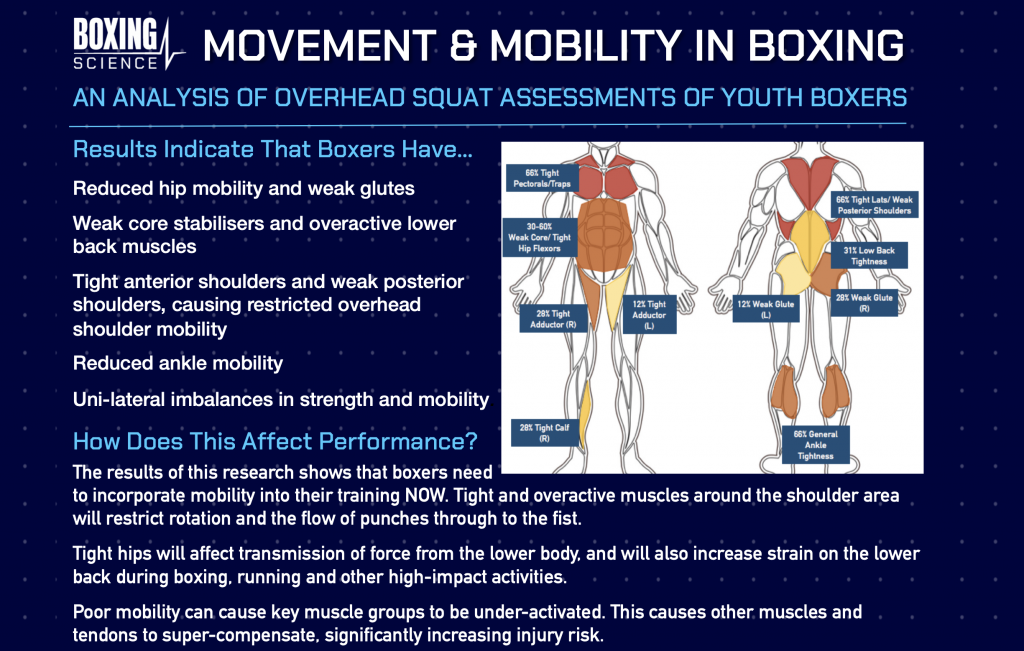

From years of testing we have established the various limitations associated with a boxer’s anatomy.

Unsurprisingly, a lack of shoulder range of motion is among the most common issues we see with boxers, 66% of boxers, in fact.

This tightness tends to develop over time due to the rounded posture associated with the boxing stance along with large punching volumes.

Anterior dominance becomes an issue as it leads to postural imbalances which cause the posterior muscles of the upper body to become under-active and weak, impairing shoulder function and mobility.

Most shoulder injuries are likely to happen due to overused and tight muscle groups, causing strain and inflamed tendons.

Full range of movement allows for maintenance of optimal length-tension relationships amongst the muscles that work across the shoulder. This can help prevent overworking of individual muscles and reduce the potential for injury.

As mentioned before, tightness in the pectorals and thoracic region can cause the humeral head to be pulled forward – increasing the chance of the shoulder to be pulled forward and causing the injuries mentioned above.

To help this, athletes should aim to improve flexibility and range of motion to reduce muscle tightness.

One key area for mobility would be to improve thoracic extension, as rounded posture of the shoulders will cause the centralization of the shoulder joint effected.

The thoracic spine is responsible for maintaining optimal protraction and retraction of the scapulae which play a significant role in protecting the shoulder during dynamic movement.

Furthermore, improving thoracic mobility can alleviate built up tension in the anterior half of the upper-body, enabling the shoulder to achieve its full range of motion when punching.

The above video outlines the warm-up we use with our athletes before boxing and strength sessions and includes various dynamic movements that target shoulder and thoracic mobility.

The main movements to look out for in the video are (with aim of improving shoulder mobility): Eagles, Windmills, Floor Slides, and rotational movements such as Spider-Man to Twist.

Also worth consideration is the use of myo-fascial release techniques around the pectoral region which can help release any taut bands of muscle in this area, reducing the extent to which the shoulders are drawn forward and inward and improving shoulder range of motion.

This can be done using a tennis or lacrosse ball and pinning it against a solid surface with your chest.

With myofascial release the aim is to find sensitive areas and continue with controlled rolls around these regions until pain or sensitivity is diminished.

SHOULDER STABILITY

Boxing is a very chaotic sport with athletes producing fast and forceful movements. This isn’t always hitting a bag where technique of delivery and impact is perfect, the punching arm can end up being forced in any direction very fast and under high forces.

Your rotator cuff is an important group of control and stability muscles that maintain “centralisation” of your shoulder joint. In other words, it keeps the shoulder ball centred over the small socket. This prevents injuries such as impingement, tendonitis, subluxations and dislocations.

By developing shoulder stability you are improving scapulohumeral rhythm, which is crucial for efficient arm movement and joint stability during punching.

If the joint is unstable – this can cause strains and tears to muscles and tendons, and even shoulder dislocations in extreme circumstances.

Click on the link below for some great rotator cuff exercises that can be used to bulletproof the shoulders and adequately prepare them for the demands of boxing.

SAFE AND EFFECTIVE SHOULDER STRENGTHENING FOR BOXING

With the concerns around shoulder mobility for boxers outlined above it is imperative to always assess the safety of various strength movements for boxers.

What mightn’t cause any evident damage in the short-term may be exposing the athlete to repeated bouts of micro-traumas, contributing to chronic issues in the long-term.

With that said as strength and conditioning coaches, we still need to strengthen the shoulder joint and its associated structures to allow the athlete to deliver powerful, punishing blows to their opponent.

ADAPTING COMPOUND LIFTS AROUND THE BOXER’S SHOULDER

The main compound lifts we use at Boxing Science are the back squat and deadlift.

These are our go-to lifts for improving lower body maximal strength and subsequently, lower-body rate of force development which is a significant contributor to punch power.

Despite the importance of these lifts, the ultimate aim of our strength and conditioning programs is to improve our athlete’s boxing performance and not to convert them to elite squatters or deadlifters.

Thus, we use variations of both of these lifts to provide a potent strength stimulus whilst minimising shoulder irritation.

ADAPTING THE BACK SQUAT

The main issue with standard barbell back squatting is the pressure the barbell exerts on shoulder joint when positioned on the back.

With any athlete it can take time to adjust to this pressure on the shoulder and due to the already prominent shoulder restrictions with boxers some of these athletes will never squat with a barbell.

This is simply because the risk vs reward ratio becomes too unfavourable and we may be causing further damage to an already problematic area.

Fortunately, we can avail of alternative set-ups for squatting and achieve much of the same benefits.

Goblet squats, safety bar squats and landmine squatting variations can all be loaded up sufficiently to induce strength adaptations and exponentially reduce stress on the shoulder joint.

ADAPTING THE DEADLIFT

At Boxing Science we program conventional deadlifts during foundational strength phases, however we tend to favour the trap-bar deadlift during strength development and max-strength phases.

The main reason for this is the stress imposed on the boxer’s shoulder in the set-up position of a conventional deadlift.

In this position, the shoulders are fixed in front of the body and boxers often struggle to maintain solid shoulder retraction throughout the entire range of motion, especially under heavy loads.

Along with increasing the chances of shoulder injury, a common consequence of this position is upper-back rounding or the “frightened cat” posture.

The trap-bar set-up , in contrast, places the shoulders in a neutral position and makes it easier for boxers to achieve and maintain solid shoulder blade retraction throughout the range of motion.

This is a win:win situation for us, as boxers are often able to lift higher loads with the trap-bar and in a safer manner compared to conventional deadlifts.

Despite being infinitely safer, we are still wary of how vulnerable the shoulders can be to injury.

Prior to sets of the trap-bar deadlifts we commonly prescribe various banded exercise that serve to activate the posterior shoulder.

This is a relatively minute detail, however can have a significant impact on the athlete’s ability to achieve the desired tension in the upper-back when setting up for a heavy deadlift.

SAFE PRESSING

When it comes to upper-body pressing, we believe that dumbbells are our FRIENDS.

Many people may argue that dumbbell exercises significantly reduce the athlete’s loading potential and thus strength gains.

Whilst this maybe true for athletes with extensive strength training backgrounds or for powerlifters, we can still derive significant strength benefits from dumbbell lifts with boxers.

This is due to their lack of exposure to structured strength training throughout their careers along with their bias towards high velocities and not high force.

Additionally, dumbbells significantly reduce internal rotation of the humeral head in the bottom position of both horizontal and vertical pressing exercises.

Internal rotation of the humeral head is something we aim to avoid as much as possible when strength training as boxers are constantly fixed in an internally rotated state during training and boxing.

A foundational movement of our programs is the dumbbell floor press which is a great exercise for teaching athletes the correct pressing positions and how to create sufficient tension in their upper back before pressing.

These are then transitioned to more advanced horizontal dumbbell pressing movements such as the standard dumbbell press and single-arm dumbbell press.

Vertically, we start the athlete off with basic dumbbell variations of the overhead press such as the half-kneeling shoulder press. These are usually performed with light loads to allow the athletes to become familiar with the movement patterns.

When the time is right and the athlete has displayed proficiency in basic vertical pressing movement patterns, heavier loads can be applied using the landmine set-up.

With vertical pressing it is also important to consider discrepancies between right and left shoulders among boxers.

Lead-hands are thrown almost three times as much as back hands and therefore programming single-arm variations may be appropriate to avoid compounding strength imbalances between the two sides.

With these pressing exercise adjustments we can develop high levels of strength and power, allowing our athletes to punch harder and more explosively without pre-disposing our athletes to injury.

SUMMARY

The shoulder joint is a ball and socket joint and has the greatest range of motion available to it out of all bodily joints. However the shoulder’s excessive mobility contributes to it’s vulnerability, especially among boxers.

At Boxing Science we place specific focus on targeting shoulder and thoracic mobility in our warm-ups to enhance shoulder function and rotation during punching.

Squatting, deadlifting and pressing exercises can be adjusted to reduce strain on the shoulder, whilst still being able to expose the athlete to potent stimuli for strength and power development.