PLYOMETRICS FOR BOXING

Are Plyometrics beneficial for Boxing?

Plyometrics are a widely utilised training modality in many sporting and athletic settings to help boost explosive performance.

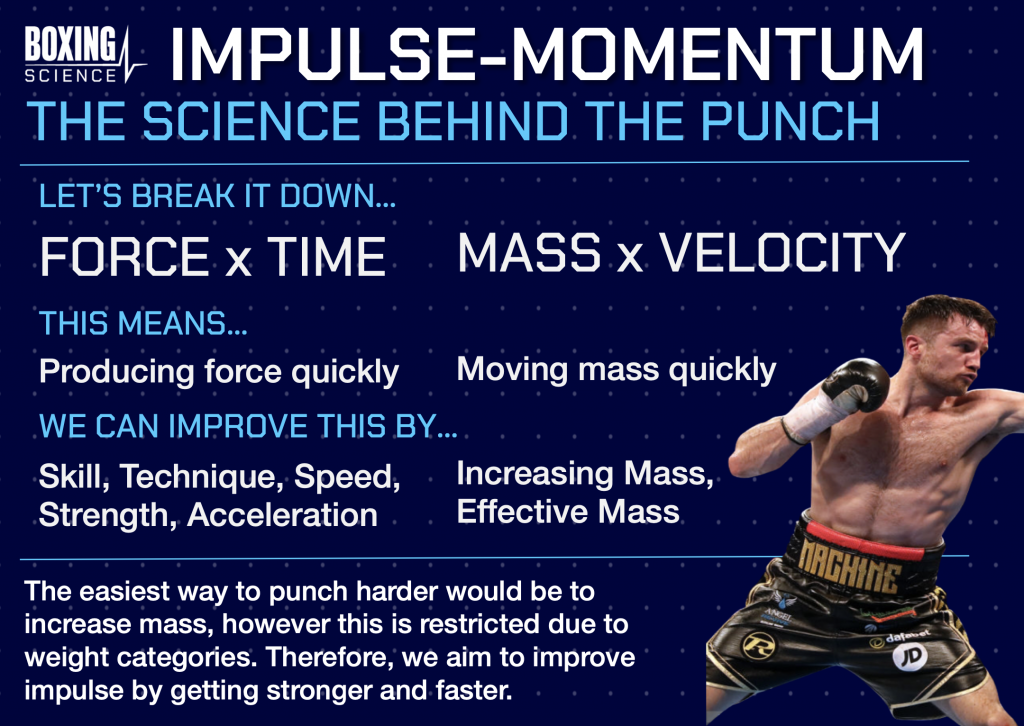

Plyometric training is primarily used to improve reactive strength which facilitates improved rate of force development and impulse, therefore contributing to improved performance during explosive athletic tasks such as jumping, sprinting and changing direction.

But why use Plyometrics in Boxing?

Our research at Boxing Science shows that increased jump height strongly correlates with punch force. This means that the higher you can jump… the harder you can punch.

The physiological adaptation we need to target is increased rate of force development (RFD). We can increase RFD by improving max strength, then working down the load-velocity curve towards lighter and more explosive movements.

Here are the potential transfer benefits for Boxing performance;

- Increases the Rate of Force Development (RFD) – this is vital for punch force and hand speed

- Improves speed, footwork, balance and movement skills

- Reduces likelihood of injury

- Can acutely increase motor unit recruitment – Warm-Ups!

- Improve eccentric utilisation / stretch-shortening cycle – important for single and combination punching

You now know the benefits… but how to integrate this into a program?

What kind of plyometrics are best to use? How to progress plyometrics in a training program? When to use them in a session, how many reps and how often?

These are just some of the questions we receive at Boxing Science. It seems that many understand the benefits, but struggle to implement them as part of a structured program.

In this article, we share;

- The science behind plyometrics

- Why we use plyometrics for Boxing

- When to use them in a training session

- The Boxing Science Plyometric training model

- Exercises to improve reactive strength

- Single leg plyometrics

WHAT ARE PLYOMETRICS?

The term plyometrics is a broad one that includes exercises which utilise and exploit the stretch shortening cycle (SSC) and challenge our neuromuscular systems ability to produce large amounts of force in short periods of time e.g jumping, bounding, running and throwing.

The stretch shortening cycle is a natural neuromuscular function and refers to a rapid pre-stretch of muscle fibres prior to performing an explosive concentric contraction.

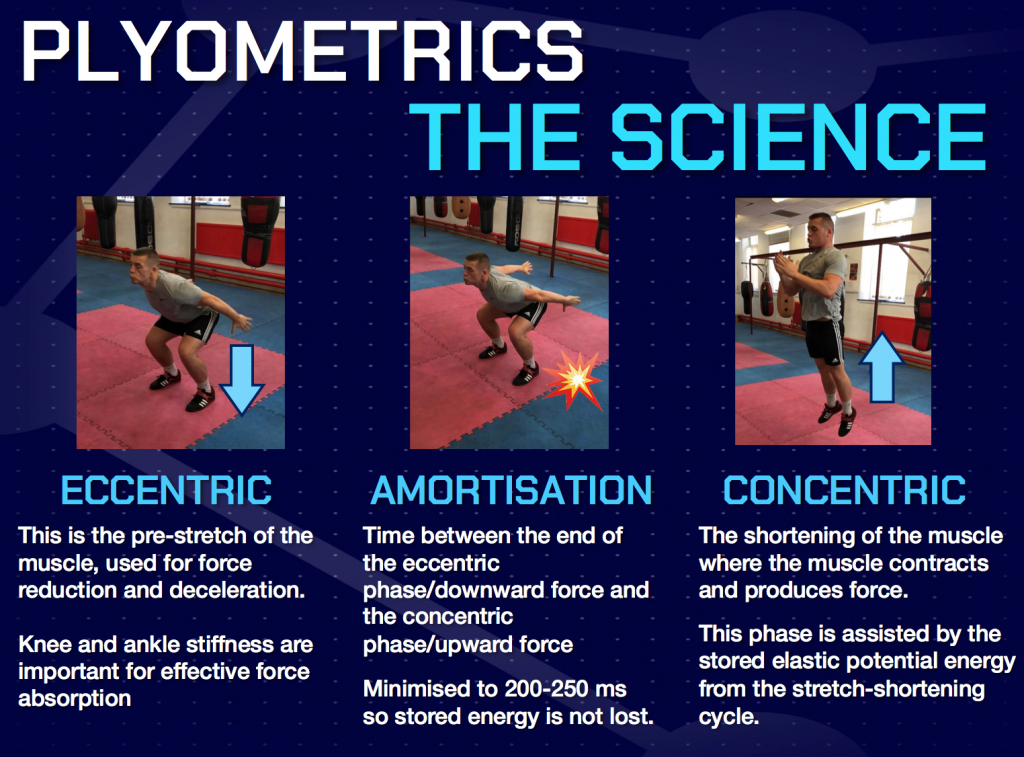

There are three distinct phases of the stretch shortening cycle:

Eccentric: This refers to the stretching of the muscle fibres and is used for force absorption/force reduction. During this phase elastic energy is stored which can then be used in the subsequent concentric contraction.

Amortisation: This is the length of time between eccentric (lengthening/force absorption/downward phase) and concentric (shortening/force production/upward phase) contractions and should be minimised to between 200-250ms so stored energy isn’t lost.

Concentric: This is the phase where muscle fibres are shortened and the muscle contracts and is enhanced by the stored elastic energy from the stretch shortening cycle.

The combination of eccentric and concentric muscle actions has been shown to elicit more forceful and efficient concentric contractions compared to performing concentric contractions, exclusively.

A classic example of this is the use of a dip prior to performing a maximal vertical jump effort compared to jumping from an erect position.

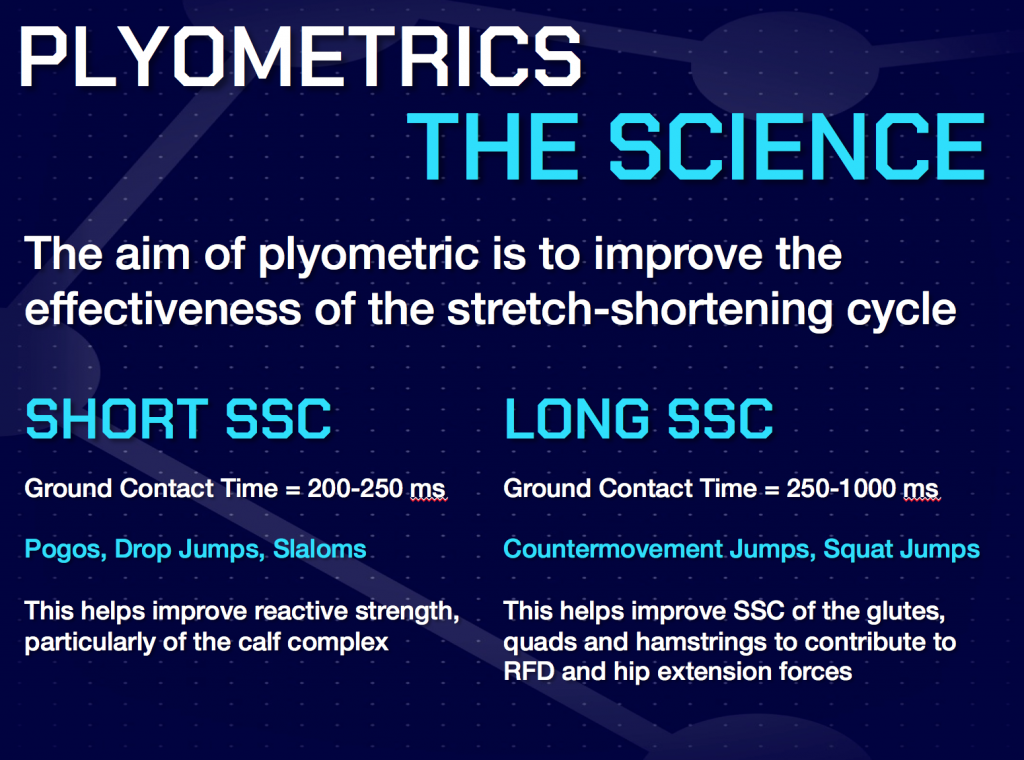

Stretch shortening cycle activities can be categorised as short and long SSC, depending on the length of ground contact associated with a given movement.

Long SSC activities tend to have a ground contact time 250-1000 milliseconds (e.g Countermovement jump, broad jump, depth jumps), whereas short SSC movements generally display a ground contact of 200-250 milliseconds, similar to the speed/sound of a clap (e.g ankle hops, repeated hurdle hops and drop jumps).

Repeated exposure to long and short stretch shortening cycle movements, facilitates improvements in impulsive qualities of muscular performance including speed strength and reactive strength.

Such impulsive qualities are important for boxers as they contribute to the athlete’s ability to produce substantial levels of force in a short period of time which is an integral aspect of many actions in the ring, most notably punching.

ADAPTATIONS TO PLYOMETRIC TRAINING

Adaptations to plyometric training may be thought of as muscular and neuromuscular.

Muscular adaptations that have been reported following plyometric training include improved activation, force output and maximal shortening velocity of fast twitch or type II muscle fibres.

Proposed neuromuscular adaptations that can be achieved through plyometric training include improved motor unit recruitment, improved speed at which these motor units are recruited and decreased autogenic inhibition.

For a more in depth explanation of these neuromuscular adaptations see our Road To Max Strength article here:

BENEFITS OF PLYOMETRICS FOR BOXING

Overall, the adaptations derived from plyometric training help improve a boxer’s ability to utilise the stretch shortening cycle and express large amounts of force, rapidly, which is a key aim of our training programs at boxing science due to the profound impact rate of force development has on the punching action.

Plyometrics are a particularly useful tool for strength and conditioning coaches in boxing as high training loads and compromised recovery practices limit the amount of maximal strength training, which is commonly used to initially improve stretch shortening cycle function, that can be performed with these athletes

Using plyometrics, we can also improve footwork, speed and balance which are vital aspects of boxing in terms of managing distance, moving in and out of range and ring control.

Plyometrics can also be used for short term or acute enhancements in performance due to their ability to fire up the nervous system and are, therefore, a viable option to include in the warm up prior to strength or boxing training sessions as well as before a fight.

Finally, plyometrics can help improve the strength and robustness of the tendons in the lower body, particularly around the ankle. This is an important injury prevention strategy for boxers when we consider the amount of time boxers spend on their toes and the repetitive short ground contacts associated with the bounce or rhythm boxers display in the ring.

WHEN TO PUT INTO THE PROGRAMME?

We incorporate plyometric activities into our extended warm ups before our strength training sessions and also before boxing sessions.

During speed-strength and taper phases explosive plyometrics become key exercises in the session.

EXTENDED WARM-UP

Short SSC and long SSC plyometrics feature in our extended warm ups.

Short SSC exercises tend to be performed for 10-15 Reps x 3-4 Sets.

Long SSC exercises: 3-5 Reps x 3-4 Sets.

SPEED-STRENGTH PHASE

Light loaded jumps with 30-40% 1RM are key exercises during these phases and are performed for 3-5 Reps x 3-5 Sets.

Trunk and core plyometrics also feature prominently in this phase.

Exercises such as kneeling med ball slams, rotational med ball throws and pallof rotations are performed for 6-8 Reps each side x 3-4 Sets.

TAPER PHASE

Plyometrics in the taper phase are predominately bodyweight and short in ground contact.

Drop jumps, advanced pogos, ice-skater progressions and explosive core plyometrics using the medicine ball are performed during the taper.

Short SSC plyometrics: 5-8 Reps x 3-4 Sets.

Medicine ball core exercises: 3-6 Reps each side x 3-4 Sets.

Watch how we taper below

THE BOXING SCIENCE PLYOMETRIC JOURNEY

Evidently, plyos are a beneficial training tool to improve speed and power and that will transfer to improved performance of dynamic athletic movements and can have specific transfer to boxing.

As such, the temptation can be to jump into high intensity plyometric training from the outset, however, there are unique challenges and considerations that must be addressed when incorporating plyometric training with boxers and other combat sports.

These considerations include the impact calorie deficits can have on recovery from high intensity strength training, boxer’s relatively low strength levels compared to athletes in other sports and movement limitations/dysfunctions often displayed by boxers due to prolonged periods of time in the boxing stance.

We also need to think about how boxers are already well adapted to fast SSC movements due to the short ground contacts associated with movement in the ring, as well as understanding that boxers will tend to struggle with advanced progressions such as single leg variations and exercises that require faster rates of stretch/higher eccentric demand.

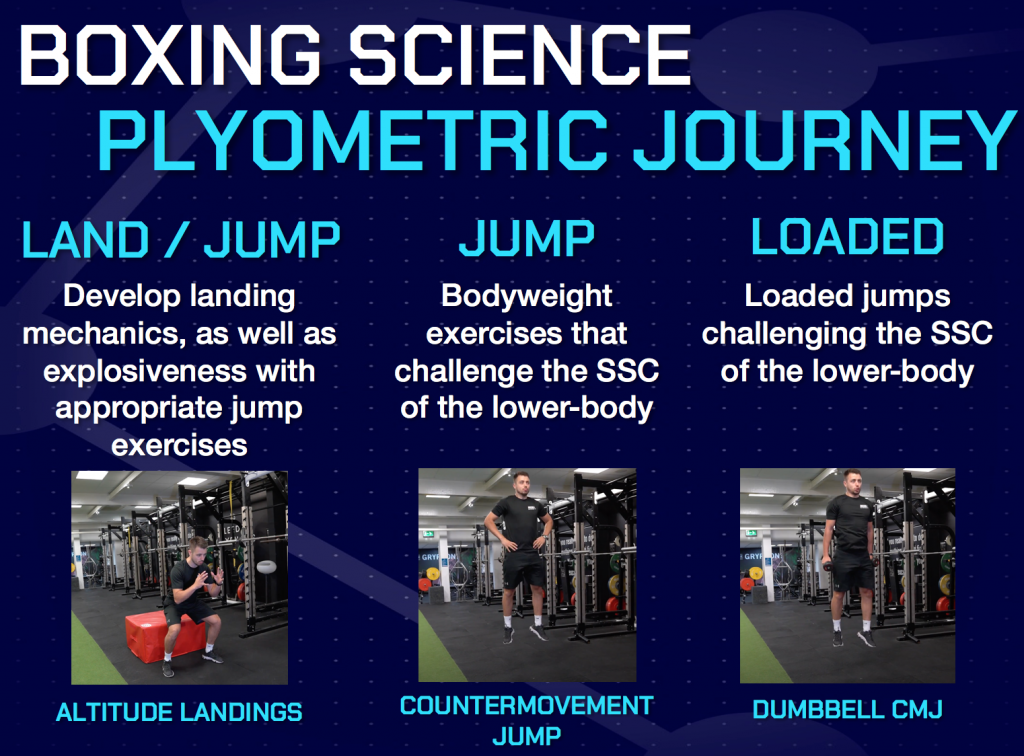

The way we integrate safe and effective plyometric training into our programs is through our plyometric training journey which has three key phases:

- Land/Jump

- Jump

- Loaded Jumps

As mentioned above our plyometric training journey has three phases and is based upon the developing the.

These phases are synonymous with the phases of the stretch shortening cycle.

We begin our plyometric journey with the land/jump phase as this focuses on mastering aspects of force absorption and eccentric utilisation.

It’s important not to skip or overlook this stage as the eccentric component of any stretch shortening cycle activity determines the length of the amortisation phase which dictates the success or force output of the concentric phase.

Having established solid landing mechanics and improved our athletes’ eccentric utilisation capabilities we then switch our focus to producing as much force as possible in a short time frame using jumping and loaded jump exercises.

PHASE 1: LAND/JUMP

This first phase of our plyometric journey usually features bodyweight exercises that develop landing mechanics and explosiveness through programming of appropriate jumping exercises.

The primary objectives of this phase is to improve our athletes eccentric utilisation and their ability to absorb force before we start focusing on producing force in subsequent training phases.

A eluded to previously, eccentric utilisation is also important for maximising concentric force output which is a key contributor to jump height and as we know, boxer’s who jump higher tend to PUNCH HARDER.

Common exercises used in this phased include snap downs, landing mechanic drills and altitude landings from progressively higher heights.

During this phase, we also want to consider the desire of our athlete’s to get fast and explosive in the short term, perhaps in preparation for their upcoming fight.

To do this we use carefully selected jumping exercises that enable our athletes to express force whilst minimising exposure to the eccentric stress associated landing from a jump.

A prime example of this type of jump is a box jump.

Jumping on to a box means we can develop the stretch short shortening cycle of the lower body and introduce the athlete to producing high levels of force, rapidly, without increasing injury risk.

Usually this phase is introduced with new athletes on the program or if boxers who have been with us for quite awhile have recently had a long lay off we will reintroduce these foundational exercises.

The duration of this phase will ultimately depend on the proficiency the athlete displays in the exercises, however, usually this phase lasts a minima of 6 weeks, particularly for new athletes on the program.

PHASE 2: JUMP

In this phase we begin to introduce bodyweight exercises that challenge the stretch shortening cycle of the lower body.

Progressing from a sole focus on absorbing force, we are now looking at how capable our athletes are at transferring this stored elastic energy to forceful concentric muscle actions.

Common exercises in this phase include rapid countermovement jumps, repeated, countermovement jumps and depth jumps (stepping off a box and performing a countermovement jump).

The goal of this phase is to maximise the amount of force the athlete can produce in a short period of time using his or her own bodyweight, and therefore promoting improvements in rate of force development.

This is one of the main reasons we tend to avoid using horizontal jump variations during this phase as, among boxers, these jumps limit force expression due to difficulties with the landing mechanics associated with these jump variations.

Additionally we want to promote forceful and rapid triple extension of the foot knee and hip as this translates to the transmission of force during a punching action.

This triple extension tends to be limited in boxers during horizontal jumps due to the focus placed on landing correctly and not producing as much force as possible.

These type of jumping activities can be incorporated into warm ups prior to strength or boxing training sessions as a means of potentiating the nervous system prior to the session.

We try to keep some type of jumping activity in our program throughout training camp as they promote speed and explosive movement even during training phases when the bulk of the session may involve slower activities such as heavy squats and deadlifts.

As part of an extended warm up jumps are usually performed for 3-5 Repetitions for 3 Sets.

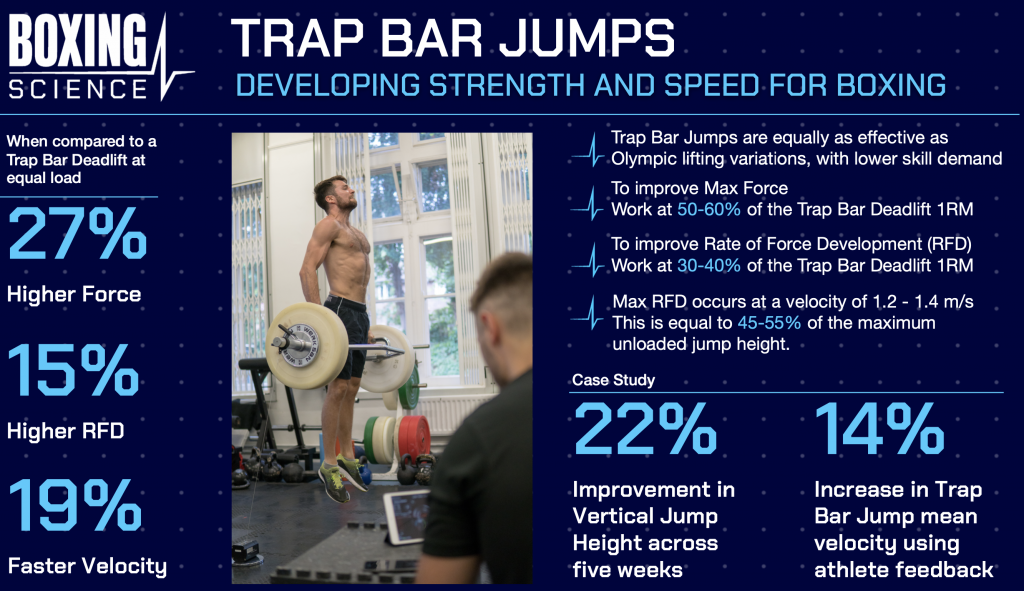

PHASE 3 LOAD

This is the most advanced stage of our plyometric training journey and entails further development of the stretch shortening cycle through the introduction of loaded jump variations.

It is important to consider the athletes strength levels before moving on to this phase.

Ideally the land/jump and jump phases are coinciding with strength and and maximal strength development as this will enable the athlete to really get the most out of this third phase in terms of force production and the rate at which this force is produced.

We usually apply load to jumping exercises using dumbbells, a barbell or a trap bar.

Staple exercises during this phase include dumbbell countermovement jumps, repeated dumbbell countermovement jumps, accentuated dumbbell jumps, barbell countermovement jumps and trap bar jumps.

Exercises during this phase are also mainly performed as part of an extended warm up usually for 3-5 repetitions by 3-4 sets.

We also use accentuated jumps with bands or dumbbells when performing contrast sets for the lower body.

Trap bar jumps and barbell countermovement jumps frequently become key exercises during strength-speed and speed-strength phases and may be performed for 3-5 Reps and 3-5 Sets as part of the main session.

Barbell and trap bar jumps are considered the most advanced exercises and need to be seen as a point where we would like our athletes to get to.

The barbell and trap bar allow for heavier loads to be lifted explosively and in a ballistic manner allowing us to target and develop fast twitch muscle fibres and improve lower body rate of force development.

Improve Reactive Strength with Short Ground Contact Time

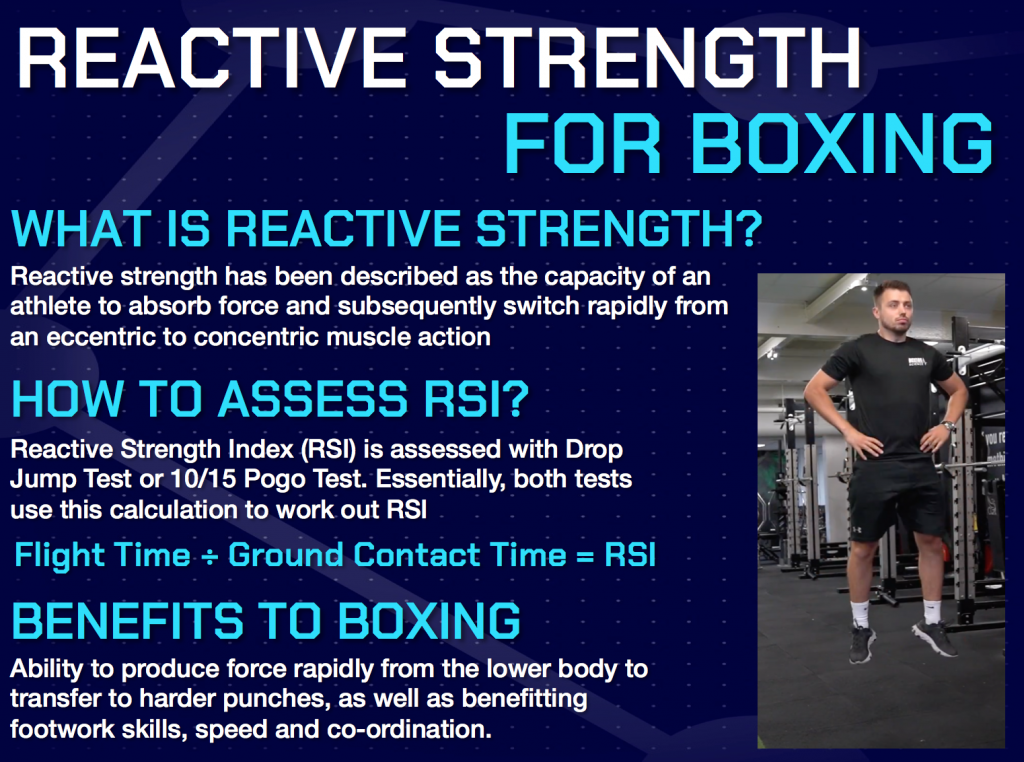

Reactive strength has been described as the capacity of an athlete to bear a stretch load and subsequently switch rapidly from an eccentric to concentric muscle action.

Reactive Strength for Footwork

There are many reasons why boxers require good levels of reactive strength to aid their footwork skills in the ring.

- Small Accelerations and Decelerations to move

- Create OR Restrict Space

- Footwork taking place primarily on the front third of the foot

- Horizontal and Lateral Movement

- Feints, Push Away, Step Back on one or two feet

- Do it quickly or opportunities are missed

- In and out of range

- Primarily submaximal movements.

Want to find out more about footwork drills for Boxing? Check out this video below

Single Leg Plyometrics for Boxing

In boxing we’re constantly bouncing, moving in and out of range by transferring weight from front to rear leg.

We’ve highlighted many times that there are lower body muscular imbalances, and this can effect the reactive strength of the ankle joint.

This means that Single leg plyometrics are important for speed, co-ordination * reactivity to help boost explosive performance and reduce the likelihood of injury

THE PROBLEM

Due to little exposure to plyometrics, boxers may find single leg plyometrics difficult to perform

The main part of the movement will be to control the eccentric part of the movement, this can make single leg plyos dangerous and will also affect the ability to train the stretch shortening cycle and concentric phase effectively.

Here are a few ways we optimise the safety and effectiveness of our single leg plyometrics.

REDUCE FOOT CONTACT TIME

To reduce contact times we can perform assisted movements using benches, bands or going into a split stance

We use single leg pogos to target the reactivity of the calf complex and encourage short ground contact times

We use Running mechanics as a form of single leg plyos as they encourage fast contact times and explosive performance

COMPLEXITY

Making the exercise more complex with fast pogos (alternate) and slaloms can add a co-ordination challenge, which will increase muscle activity whilst keeping the contact times short.

LONG SSC

We also want to challenge the long strength-shortening cycle to develop explosive strength.

We use Ice Skaters For this as this can transfer to improvements in lateral power. This also utilises the Glutes more, which discourages the jumps from being anterior dominant.

WHEN TO USE

We use the short ground contact exercises as part of our warm-ups for conditioning sessions – as this prepares the ankle joint and Achilles for high forces during high speed running

Performing 2-3 exercises, 8-10 reps x 3 sets

We use 1 long SSC exercise for strength – this is part of an extended warm-up. 5-8 reps each side x 3 sets

SUMMARY

Plyometrics are used to develop rate of force development which is an important attribute for boxers considering the large amount of forces that have to be developed in a short space of time when throwing powerful punches.

There are three phases of any plyometric/stretch shortening cycle activity: eccentric, amortisation and concentric phases.

Our plyometric journey consists of three phases including Land/Jump, Jump and Loaded phases.